Italian-style dry pasta

let's learn to recognize quality

A clear and quick guide to truly understanding what makes pasta good, digestible, and fragrant. Beyond marketing, beyond trends: let's get back to the essence.

Pasta is a daily activity, but not all pasta is created equal. On this page, we'll explain—in a simple and clear way—what really goes into making Italian-style dried pasta : from the ingredients to the production processes, to the tricks for recognizing quality pasta at a glance.

Why talk seriously about pasta?

We often choose pasta based on habit, price, or a quick tip. But behind every shape lie raw materials, production processes, and technical choices that completely change the final result: flavor, cooking resistance, digestibility, and the ability to bind sauce.

This guide was created to give you an objective evaluation criterion : not “I like this pasta because someone said so,” but “this pasta is made well, I know why and I can recognize it.”

How to recognize well-made pasta (even without being an expert)

Four small gestures that change the way you choose pasta:

✔ Break a shape: If the inside is floury and opaque, you're looking at a slow-dried pasta. If it's glassy, it was pre-cooked while drying.

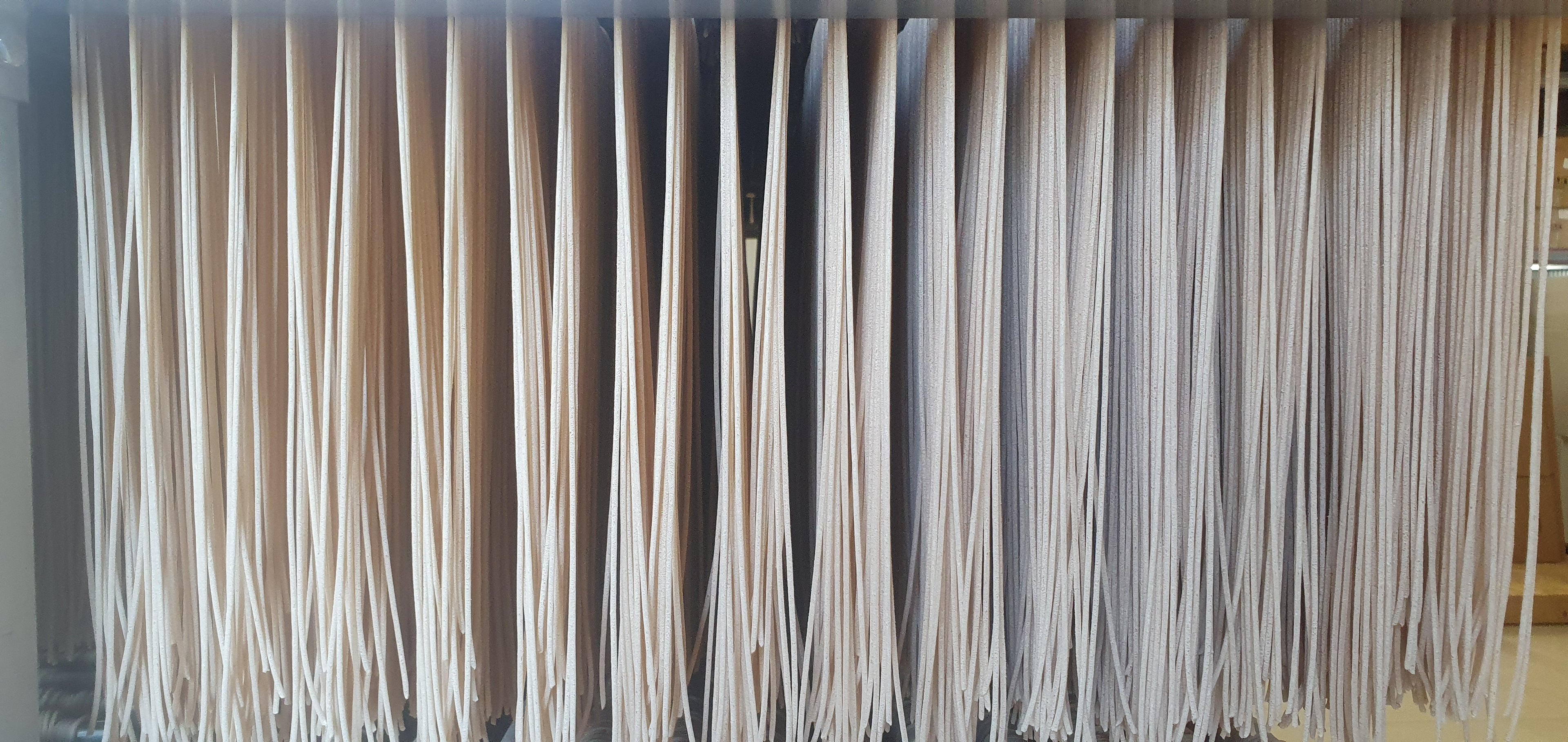

✔ Observe the surface: The natural roughness is the sign of a pasta that welcomes the sauce, not rejects it.

✔ Watch what happens during cooking: Well-made pasta holds its shape during cooking, doesn't fall apart, and stays alive.

Remember: pasta has little impact on the cost of the dish . The difference is in the taste, not in your wallet.

Does “bronze drawn” mean high quality?

No, not alone. The die is important, but it's the drying process that determines true quality. Without the proper mixing, extrusion, and drying times, pasta remains an industrial product even if "bronze" is written in large letters.

Durum wheat (Triticum durum)

- Warm, yellow-amber color

- Greater protein richness

- Higher gluten potential

- Perfect for giving strength to the pasta and keeping it al dente

Soft wheat

- White/grey colour

- Lower protein

- Excellent for leavened products, not for dry pasta

- Does not allow for a true strong gluten mesh

Why does artisanal pasta cost a little more?

Because it takes time: time to dry, time to respect the semolina, time to not pre-cook it.

On the plate, the economic difference is minimal. But the difference in taste is enormous. Here are the three main steps:

(A) DOUGH

Semolina and water meet.

The mix passes through a continuous screw machine that works slowly and precisely.

The movement and hydration allow the proteins in the semolina to combine and form the gluten mesh : a natural network that will give strength to the pasta and allow it to hold its shape during cooking.

Structure is born here. Strength is born here.

(B) EXTRUSION

The dough is pushed through a die , which determines its shape: spaghetti, penne, fusilli. A blade cuts the pasta to the desired length.

At this stage, a significant part of the surface porosity comes into play, influenced by: (1) die material, (2) extrusion speed, and (3) working temperature. A slow and controlled extrusion preserves the dough and prepares the pasta to bind the sauce better.

(C) DRYING

This is the most delicate phase. It serves to eliminate excess water until the final humidity level does not exceed 12.5% .

Drying at high temperatures causes a partial gelation of the carbohydrates: the pasta is effectively pre-cooked , with a more compact and crystalline internal structure.

Slow drying, on the other hand, leaves the semolina raw inside , creates natural porosity and returns a lively, elastic pasta, capable of holding the sauce.

Does PGI guarantee better quality?

No. It guarantees a territory and a way of working, not the origin of the grain. It's a cultural value, not an absolute proof of quality.

What is the gluten mesh?

It's the protein network that gives pasta its elasticity, firmness, and ability to stay al dente. It's formed thanks to water, energy, and the quality of the semolina.

It's the silent secret of a pasta that doesn't fall apart.

What is carbohydrate gelation?

When the pasta exceeds 81°C, the starch opens, hydrates, and becomes digestible.

If the gluten mesh is well formed, this process is harmonious: the dough is soft but whole, creamy but not sticky.

The pasta factory in the field

Our transformation begins within 15 days of milling , when the semolina fresh from the mill arrives at the pasta factory.

Here, the work of enhancing the raw materials continues, in a process that preserves their original aromas, nutrients, and flavors intact.

Each step is slow, controlled, and carried out at low temperatures, to ensure authentic, digestible pasta full of character.

What is Italian dry pasta?

Italian-style dried pasta is defined by specific legislation ( Legislative Decree 537/1992 ). To be called this, it must:

- be produced by an authorized pasta factory

- contain only durum wheat semolina and water

- have a maximum humidity of 12.5% after drying

No soft wheat flour, no additives: just durum wheat and water, processed according to clear rules.

💡 In a nutshell: A true Italian dry pasta is very simple in its recipe, but complex in its choice of wheat and the way it is processed .

Why dry pasta was born

Dried pasta originated as a method of preserving flour . Flour, if moist, can develop dangerous mold; turning it into pasta and drying it has historically been a way to make it stable and safe .

To truly understand pasta, however, you need to observe how carbohydrates behave. Inside the grain, they are preserved in the form of crystals , a structure that protects them and makes them inedible. They become digestible only after gelation , a process that occurs thanks to the combination of water and heat (above about 80°C).

This discussion also ties in with the role of "fad" diets: the demonization of carbohydrates or the obsession with the glycemic index have no basis in the physiology of a healthy individual. The body is designed to manage the absorption of sugars, and what really determines weight gain or loss is energy balance , not the order in which foods are eaten.

Durum wheat semolina vs. soft wheat flour

Durum wheat semolina and soft wheat flour are not the same thing. They are two different species, with different chemical and visual characteristics. They are often confused, but they are two different raw materials, obtained from different grains, with very different cooking behaviors. Durum wheat semolina is typically yellowish/amber , richer in protein and potential gluten, and is best suited for pasta production. Soft wheat flour , on the other hand, is whitish , has less protein, and is better suited for bread and desserts.

Nutritionally, flour products have a fairly consistent profile: approximately 330 kcal per 100 g, a protein content ranging from 13% to 18%, fiber around 10%, and a significant amount of carbohydrates. It's a high-energy-dense food, which explains, for example, why a pizza made with 300 g of flour already contains nearly 1,000 kcal.

Durum wheat (Triticum durum)

- Color: yellow/amber

- More protein

- Greater gluten potential

- Ideal for dry pasta

Soft wheat

- Color: white/grey

- Less protein

- Most used for bread, cakes, baked goods

- Not suitable on its own for real Italian dry pasta

Gluten: How it forms and why it's essential in pasta

Gluten is not a pre-existing substance in flour. It is a protein network formed when water, movement, and mechanical energy cause gliadins and glutenins to interact. This network, called the gluten mesh , is what allows dough to become elastic and resistant.

Gluten is essential because it controls the gelation of carbohydrates during cooking. A well-developed gluten network slows the process and allows the pasta to remain al dente , preventing it from falling apart. In industrial pasta, where part of the gelation occurs during production (due to high temperatures), a higher gluten content is needed to ensure the product holds up to cooking.

In artisanal pasta, however, the semolina remains raw until it is cooked at home: the gluten is developed just enough and "hyper-protein" is not necessary because quality comes from slower and more delicate processes.

How dry pasta is produced

Three phases, many technical choices that make the difference:

Dough

Durum wheat semolina and water are slowly worked in vats with a continuous screw, until the gluten mesh is formed: a protein network that gives structure to the pasta and will allow it to hold its shape during cooking.

EXTRUSION

The dough is pushed through a die (made of bronze or other materials) that shapes the pasta. This gives it its rough exterior and its ability to hold sauce.

DRYING

This is the most delicate step: excess water is removed until the humidity level drops below 12.5%.

Slow drying at low temperatures ensures a non-precooked, porous, and fragrant pasta. Rapid, hot drying, on the other hand, produces a more "crystalline" and partially precooked pasta.

The difference is evident when breaking a piece of pasta: if the inside is floury and uneven, it is slowly dried pasta; if it is glassy and crystalline , it is industrial pasta.

Why dry pasta was born

Dried pasta originated as a method of preserving flour . Flour, if moist, can develop dangerous mold; turning it into pasta and drying it has historically been a way to make it stable and safe .

To truly understand pasta, however, you need to observe how carbohydrates behave. Inside the grain, they are preserved in the form of crystals , a structure that protects them and makes them inedible. They become digestible only after gelation , a process that occurs thanks to the combination of water and heat (above about 80°C).

This discussion also ties in with the role of "fad" diets: the demonization of carbohydrates or the obsession with the glycemic index have no basis in the physiology of a healthy individual. The body is designed to manage the absorption of sugars, and what really determines weight gain or loss is energy balance , not the order in which foods are eaten.

Porosity and why it is the true discriminant of quality

Porosity allows the sauce to bind to the pasta. This isn't just an aesthetic detail: it's the combined result of:

- slow drying (leaving internal voids as the water evaporates);

- controlled extrusion, which creates surface micro-roughness.

The truth is that without good drying , even the bronze die is of little use: an industrial “bronze-drawn” pasta remains a partially pre-cooked product, therefore not very porous internally.

In artisanal pasta, however, the semolina dries slowly, forming internal cavities and allowing for more even cooking. This means the protein content required can be lower: there's no need to "force" the structure to hold it together.

Industrial vs. Artisanal: Philosophy, Processes, and Results on the Plate

Industrial production focuses on speed : more liquid doughs, rapid extrusions, aggressive drying. This results in a pre-gelatinized , very uniform dough that requires a lot of gluten and provides a less complex consistency.

Artisanal production, on the other hand, focuses on food quality : no high temperatures, long cooking times, or raw semolina until cooked at home. The result is a porous, elastic pasta, capable of holding sauces and with a much richer flavor profile.

Regarding cost, it's important to be clear: even when choosing artisanal pasta, the portion of the final dish's cost attributable to the pasta itself is minimal . A maximum of 5–15%: everything else is the sauce. Changing the sauce can save you money without sacrificing the quality of the pasta.

💡 The myth of ridged pasta: Ridges are not in themselves a sign of quality. Historically, they arose to compensate for the poor porosity of industrial pasta: they were used to allow a minimum amount of sauce to adhere to a very smooth and low-performance product. Over time, they became a commercial habit. The truth is that sauce adhesion depends almost entirely on internal porosity, drying, and the quality of the semolina , not on the ridges on the surface.

Quality is not a detail, it is a choice that starts on the field.

At Agrimò we grow our grains in Salento, we stone grind them, we knead them with pure water and let the pasta dry as nature dictates, not the clock .

For us, pasta is not an industrial product: it is the result of a supply chain that we personally control, from seed to package, following the Agrimò method .

If you've read this far, you already know: choosing the right pasta isn't a technical skill, but a cultural one.

And it's also a way to love yourself.

The Agrimò team

Discover the full range of dried pasta and join a project that combines taste, well-being, and circular sustainability .